The foghorn has been blowing nights lately here in Newport. It is rhythmic, consistent, and faint when heard from behind and some city blocks away. But it's there, alerting passing ships of a busy harbor and a jagged coastline; both a warning and a welcome, I imagine, on a night wrapped in a pale shroud.

As I sit on the porch of my house on Thames Street (pronounced THAY-MS, as if you've never heard of the river that cuts across London) in Newport, just five minutes walking to the waterfront, I listen to the foghorn and wonder why it still blows. Between GPS systems, Doppler radar, easy synchronous communication with harbormasters, weather app push notifications, and all the millions of other high-tech methods of communicating information to ships at sea, why do we still go to the trouble of blowing a foghorn or lighting a lighthouse? Surely those other methods must be in use, so why do we cling to these outmoded techniques as well?

Foghorns and lighthouses are just a single step removed from bonfires and yelling from the beach, and yet we stick with them. We keep just enough of them maintained to back up our new digital warning and communication networks, and we sell the rest of them off to become passion projects, museums, or Airbnb rentals. But they still dot our coasts and the coasts of the rest of the world, and we hear the horns blowing on foggy nights and are reminded that our contemporary systems have antecedents in a pre-digital history, a history in which the brightness of a lighthouse lamp or the volume of a foghorn could change the fates of those living their lives on the water and the people waiting for them on shore.

---

The foghorn blows, and the fog changes light. I walked down to a deserted corner of the harbor earlier and stood on the edge of the island. Across the water a few hundred yards in front of me, a finger of land cut into the sea, with docks and cedar-sided buildings long since converted from their original industrial purpose into cafes and bars. Refracting through the water in the air, the bluish mercury vapor pole lights came to me tinted green, and I thought of Gatsby staring out over the water, seeing Daisy in that green light over the dock.

That light, turned green likely by the fog, is something to strive for, but it's unclear whether he desires the chance to build a glorious future or relive a beautiful past. As Nick Carraway reflects on Gatsby's death, he engages this circular desire. The boat sails against the current, but for every thrust forward it moves backward as well. The future recedes beyond our grasp, but perhaps if we lean forward just a bit farther we'll be able to catch its edge and pull ourselves into it. But of course, as Gatsby learns, this is a lie we tell ourselves to explain the sore muscles from all that reaching. We cannot live in any time but the present, no matter how much money or how many friends and party guests we have.

---

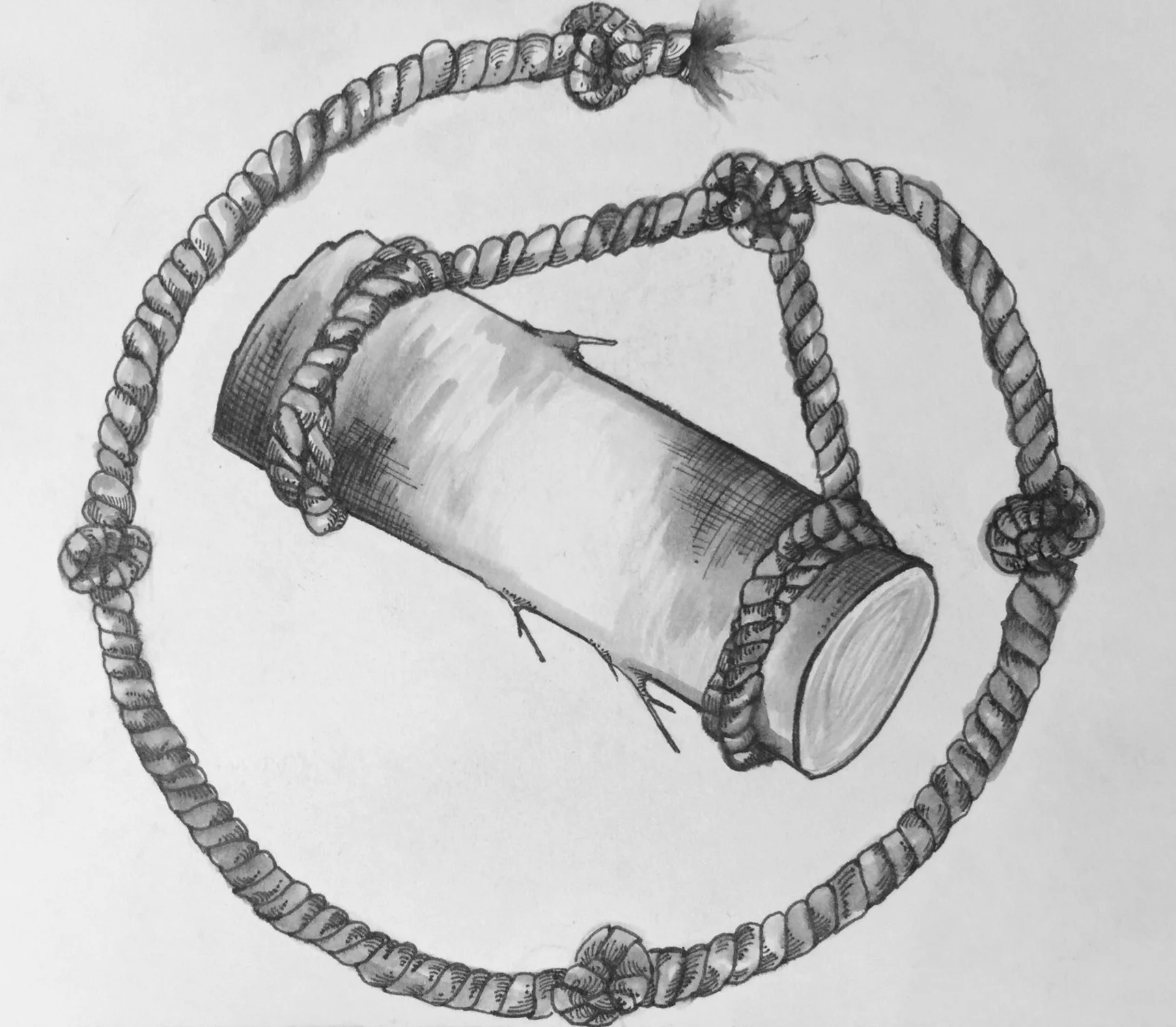

I do sometimes wonder if that's why I'm here, learning traditional methods to build sailing vessels from wood. I wonder if I'm chasing a past in the guise of a future. In my case the past is not my own, but a shared one, and in pursuing it I wonder if I'm running forward in an attempt to chase down something that is actually behind me.

If that's the case, however, it does seem like I'll be running alongside a lot of other people in pursuit of the same thing. I'm not a Luddite smashing the machines in the factory, but I am in search of some way to make a living and a life that has been touched and shaped and created by human hands. It's possible, however, that this life is a figment of my imagination.

My previous career brought me to many far-flung corners of the world, and I'm enormously grateful for the opportunities it afforded me, But now I'm ready for something different, something more material, something more vertically organized than horizontal. I don't want to spread myself out to cover as much of the world (or the ministry-mandated curriculum) as I can. Instead, I want to dive into things, I want to peer inside and beneath and to set myself in the ground and learn how they work and how to make them myself.